Are you solving the right problems?

By Thomas Wedell-Wedellsborg via HBR.org

How good is your company at problem solving? Probably quite good, if your managers are like those at the companies I’ve studied. What they struggle with, it turns out, is not solving problems but figuring out what the problems are. In surveys of 106 C-suite executives who represented 91 private and public-sector companies in 17 countries, I found that a full 85% strongly agreed or agreed that their organizations were bad at problem diagnosis, and 87% strongly agreed or agreed that this flaw carried significant costs. Fewer than one in 10 said they were unaffected by the issue. The pattern is clear: Spurred by a penchant for action, managers tend to switch quickly into solution mode without checking whether they really understand the problem.

It has been 40 years since Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and Jacob Getzels empirically demonstrated the central role of problem framing in creativity. Thinkers from Albert Einstein to Peter Drucker have emphasized the importance of properly diagnosing your problems. So why do organizations still struggle to get it right?

Part of the reason is that we tend to overengineer the diagnostic process. Many existing frameworks—TRIZ, Six Sigma, Scrum, and others—are quite comprehensive. When properly applied, they can be tremendously powerful. But their very thoroughness also makes them too complex and time-consuming to fit into a regular workday. The setting in which people most need to be better at problem diagnosis is not the annual strategy seminar but the daily meeting—so we need tools that don’t require the entire organization to undergo weeks-long training programs.

But even when people apply simpler problem-diagnosis frameworks, such as root cause analysis and the related 5 Whys questioning technique, they often find themselves digging deeper into the problem they’ve already defined rather than arriving at another diagnosis. That can be helpful, certainly. But creative solutions nearly always come from an alternative definition of your problem.

Through my research on corporate innovation, much of it conducted with my colleague Paddy Miller, I have spent close to 10 years working with and studying reframing—first in the narrow context of organizational change and then more broadly. In the following pages I offer a new approach to problem diagnosis that can be applied quickly and, I’ve found, frequently leads to creative solutions by unearthing radically different framings of familiar and persistent problems. To put reframing in context, I’ll explain more precisely just what this approach is trying to achieve.

The Slow Elevator Problem

Imagine this: You are the owner of an office building, and your tenants are complaining about the elevator. It’s old and slow, and they have to wait a lot. Several tenants are threatening to break their leases if you don’t fix the problem.

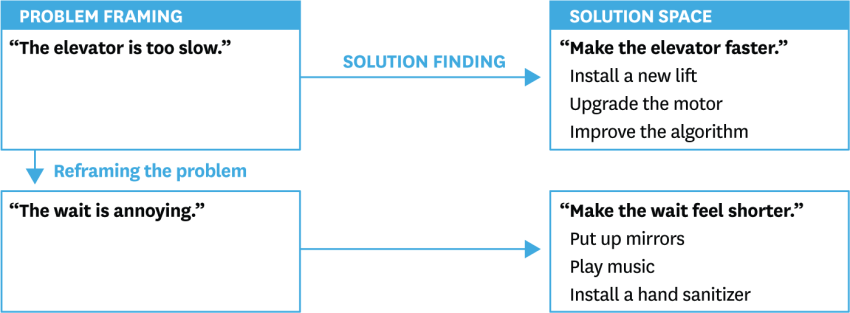

When asked, most people quickly identify some solutions: replace the lift, install a stronger motor, or perhaps upgrade the algorithm that runs the lift. These suggestions fall into what I call a solution space: a cluster of solutions that share assumptions about what the problem is—in this case, that the elevator is slow. This framing is illustrated below.

However, when the problem is presented to building managers, they suggest a much more elegant solution: Put up mirrors next to the elevator. This simple measure has proved wonderfully effective in reducing complaints, because people tend to lose track of time when given something utterly fascinating to look at—namely, themselves.

The mirror solution is particularly interesting because in fact it is not a solution to the stated problem: It doesn’t make the elevator faster. Instead it proposes a different understanding of the problem.

Note that the initial framing of the problem is not necessarily wrong. Installing a new lift would probably work. The point of reframing is not to find the “real” problem but, rather, to see if there is a better one to solve. In fact, the very idea that a single root problem exists may be misleading; problems are typically multicausal and can be addressed in many ways. The elevator issue, for example, could be reframed as a peak demand problem—too many people need the lift at the same time—leading to a solution that focuses on spreading out the demand, such as by staggering people’s lunch breaks.

Identifying a different aspect of the problem can sometimes deliver radical improvements—and even spark solutions to problems that have seemed intractable for decades. I recently saw this in action when studying an often overlooked problem in the pet industry: the number of dogs in shelters.

America’s Dog-Adoption Problem

Dogs are very popular in America: Industry statistics suggest that more than 40% of U.S. households have one. But this fondness for dogs has a downside: According to estimates by the ASPCA, one of the largest animal-welfare groups in the United States, more than 3 million dogs enter a shelter each year and are put up for adoption.

Shelters and other animal-welfare organizations work hard to raise awareness of this issue. A typical ad or poster will show a neglected, sad-looking dog, carefully chosen to evoke compassion, along with a line such as “Save a life—adopt a dog” or perhaps a request to donate to the cause. Through this and other initiatives, this notoriously underfunded system manages to get about 1.4 million dogs adopted each year. But that leaves more than a million unadopted dogs—and doesn’t account for the many cats and other pets in the same situation. There is just a limited amount of compassion to go around. So despite the impressive efforts of shelters and rescue groups, the shortage of pet adopters has persisted for decades.

Lori Weise, the founder of Downtown Dog Rescue in Los Angeles, has demonstrated that adoption is not the only way to frame the problem. Weise is one of the pioneers of an approach that is currently spreading within the industry—the shelter intervention program. Rather than seek to get more dogs adopted, Weise tries to keep them with their original families so that they never enter shelters in the first place. It turns out that about 30% of the dogs that enter a shelter are “owner surrenders,” deliberately relinquished by their owners. In a volunteer-driven community united by a deep love of animals, those people have often been heavily criticized for heartlessly discarding their pets as if they were just another consumer good. To prevent dogs from ending up with such “bad” owners, many shelters, despite their chronic overpopulation, require potential adopters to undergo laborious background checks.

Weise has a different take. “Owner surrenders are not a people problem,” she says. “By and large, they are a poverty problem. These families love their dogs as much as we do, but they are also exceptionally poor. We’re talking about people who in some cases aren’t entirely sure how they will feed their kids at the end of the month. So when a new landlord suddenly demands a deposit to house the dog, they simply have no way to get the money. In other cases, the dog needs a $10 rabies shot, but the family has no access to a vet, or may be afraid to approach any kind of authority. Handing over their pet to a shelter is often the last option they believe they have.”

Weise started her program in April 2013, collaborating with a shelter in South Los Angeles. The idea is simple: Whenever a family comes in to hand over a pet, a staff member asks without judgment if the family would prefer to keep the pet. If the answer is yes, the staff member tries to help resolve the problem, drawing on his or her network and knowledge of the system.

Within the first year it was clear that the program was a remarkable success. In prior years Weise’s organization had spent an average of $85 per pet it helped. The new program brought that cost down to about $60 while keeping shelter space free for other animals in need. And, Weise told me, that was just the immediate impact: “The wider effect on the community is the real point. The program helps families learn problem solving, lets them know their rights and responsibilities, and teaches the community that help is available. It also shifted the industry’s perception of the pet owners: We found that when offered assistance, a full 75% of them actually wanted to keep their pets.”

You won’t know which problems can benefit from being reframed until you try.

As of this writing, Weise’s program has helped close to 5,000 pets and families and has gained the formal support of the ASPCA. Weise has released a book, First Home, Forever Home, that explains to other rescue groups how to run an intervention program. Thanks to her reframing of the problem, overcrowded shelters may someday be a thing of the past.

How might you find a similarly insightful reframing for your problem?

Seven Practices for Effective Reframing

In my experience, reframing is best taught as a quick, iterative process. You might think of it as a cognitive counterpoint to rapid prototyping.

The practices I outline here can be used in one of two ways, depending on how much control you have over the situation. One way is to methodically apply all seven to the problem. That can be done in about 30 minutes, and it has the benefit of familiarizing everyone with the method.

The other way is suitable when you don’t control the situation and have to scale the method according to how much time is available. Perhaps a team member ambushes you in the hallway and you have only five minutes to help him or her rethink a problem. If so, simply select the one or two practices that seem most appropriate.

Five minutes may sound like too little time to even describe a problem, much less reframe it. But surprisingly, I have found that such short interventions are often sufficient to kick-start new thinking—and once in a while they can trigger an aha moment and radically shift your view of a problem. Proximity to your own problems can make it easy to get lost in the weeds, endlessly ruminating about why a colleague, a spouse, or your children won’t listen. Sometimes all you need is someone to suggest, “Well, could the trouble be that you are bad at listening to them?”

Of course, not all problems are that simple. Often multiple rounds of reframing—interspersed with observation, conversation, and prototyping—are necessary. And in some cases reframing won’t help at all. But you won’t know which problems can benefit from being reframed until you try. Once you’ve mastered the five-minute version, you can apply reframing to pretty much any problem you face.

Here are the seven practices:

1. Establish legitimacy.

It’s difficult to use reframing if you are the only person in the room who understands the method. Other people, driven by a desire to find solutions, may feel that your insistence on discussing the problem is counterproductive. If the group has a power imbalance, such as when you’re facing clients or more-senior colleagues, they may well shut you down before you even get started. And even powerful executives may find it hard to use the method when people are accustomed to getting answers rather than questions from their leaders.

Your first job, therefore, is to establish the method’s legitimacy within the group, creating the conversational space necessary to employ reframing. I suggest two ways to do this. The first is to share this article with the people you are meeting. Even if they don’t read it, simply seeing it may persuade them to listen to you. The second is to relate the slow elevator problem, which is my go-to example when I have less than 30 seconds to explain the concept. I have found it to be a powerful way to quickly explain reframing—how it differs from merely diagnosing a problem and how it can potentially create dramatically better results.

2. Bring outsiders into the discussion.

This is the single most helpful reframing practice. I saw it in action eight years ago when the management team of a small European company was wrestling with a lack of innovation in its workforce. The managers had recently encountered a specific innovation training technique they all liked, so they started discussing how best to implement it within the organization.

Sensing that the group lacked an outside voice, the general manager asked his personal assistant, Charlotte, to take part in their discussion. “I’ve been working here for 12 years,” Charlotte told the group, “and in that time I have seen three different management teams try to roll out some new innovation framework. None of them worked. I don’t think people would react well to the introduction of another set of buzzwords.”

Charlotte’s observation prompted the managers to realize that they had fallen in love with a solution—introducing an innovation framework—before they fully understood the problem. They soon concluded that their initial diagnosis had been wrong: Many of their employees already knew how to innovate, but they didn’t feel very engaged in the company, so they were unlikely to take initiative beyond what their job descriptions mandated. What the managers had first framed as a skill-set problem was better approached as a motivation problem.

They abandoned all talk of innovation workshops and instead focused on improving employee engagement by (among other things) giving people more autonomy, introducing flexible working hours, and switching to a more participatory decision-making style. The remedy worked. Within 18 months workplace satisfaction scores had doubled and employee turnover had fallen dramatically. And as people started bringing their creative abilities to bear at work, financial results improved markedly. Four years later the company won an award for being the country’s best place to work.

As this story shows, getting an outsider’s perspective can be instrumental in rethinking a problem quickly and properly. To do so most effectively:

Look for “boundary spanners.” As research by Michael Tushman and many others has shown, the most useful input tends to come from people who understand but are not fully part of your world. Charlotte was close enough to the front lines of the company to know how the employees really felt, but she was also close enough to management to understand its priorities and speak its language, making her ideally suited for the task. In contrast, calling on an innovation expert might well have led the team’s members further down the innovation path instead of inspiring them to rethink their problem.

Choose someone who will speak freely. By virtue of her long tenure and her closeness to the general manager, Charlotte felt free to challenge the management team while remaining committed to its objectives. This sense of psychological safety, as Harvard’s Amy C. Edmondson calls it, has been proved to help groups perform better. You might consider turning to someone whose career advancement will not be determined by the group in question or who has a track record of (constructively) speaking truth to power.

Expect input, not solutions. Crucially, Charlotte did not try to provide the group with a solution; rather, her observation made the managers themselves rethink their problem. This pattern is typical. By definition, outsiders are not experts on the situation and thus will rarely be able to solve the problem. That’s not their function. They are there to stimulate the problem owners to think differently. So when you bring them in, ask them specifically to challenge the group’s thinking, and prime the problem owners to listen and look for input rather than answers.

3. Get people’s definitions in writing.

It’s not unusual for people to leave a meeting thinking they all agree on what the problem is after a loose oral description, only to discover weeks or months later that they had different views of the issue. Moreover, a successful reframing may well lurk in one of those views.

For instance, a management team may agree that the company’s problem is a lack of innovation. But if you ask each member to describe what’s wrong in a sentence or two, you will quickly see how framings differ. Some people will claim, “Our employees aren’t motivated to innovate” or “They don’t understand the urgency of the situation.” Others will say, “People don’t have the right skill set,” “Our customers aren’t willing to pay for innovation,” or “We don’t reward people for innovation.” Pay close attention to the wording, because even seemingly inconsequential word choices can surface a new perspective on the problem.

I saw a memorable demonstration of this when I was working with a group of managers in the construction industry, exploring what they could do as individual leaders to deliver better results. As we tried to identify the barriers each one faced, I asked them to write their problems on flip charts, after which we jointly analyzed the statements. The very first comment from the group had the greatest impact: “Almost none of the definitions include the word ‘I.’” With one exception, the problems were consistently worded in a way that diffused individual responsibility, such as “My team doesn’t…,” “The market doesn’t…,” and, in a few cases, “We don’t…” That one observation shifted the tenor of the meeting, pushing the participants to take more ownership of the challenges they faced.

These individual definitions of the problem should ideally be gathered in advance of a discussion. If possible, ask people to send you a few lines in a confidential e-mail, and insist that they write in sentence form—bullet points are simply too condensed. Then copy the definitions you’ve collected on a flip chart so that everyone can see them and react to them in the meeting. Don’t attribute them, because you want to ensure that people’s judgment of a definition isn’t affected by the definer’s identity or status.

Receiving these multiple definitions will sensitize you to the perspectives of other stakeholders. We all appreciate in theory that others may experience a problem differently (or not see it at all). But as demonstrated in a recent study by Johannes Hattula, of Imperial College London, if managers try to imagine a customer’s perspective themselves, they typically get it wrong. To understand what other stakeholders think, you need to hear it from them.

4. Ask what’s missing.

When faced with the description of a problem, people tend to delve into the details of what has been stated, paying less attention to what the description might be leaving out. To rectify this, make sure to ask explicitly what has not been captured or mentioned.

Recently I worked with a team of senior executives in Brazil who had been asked to provide their CEO with ideas for improving the market’s perception of the company’s stock price. The team had expertly analyzed the components affecting a stock’s value—the P/E ratio forecast, the debt ratio, earnings per share, and so on. Of course, none of this was news to the CEO, nor were these factors particularly easy to affect, leading to mild despondency on the team.

But when I prompted the executives to zoom out and consider what was missing from their definition of the problem, something new came up. It turned out that when external financial analysts asked to speak with executives from the company, the task of responding was typically delegated to slightly more junior leaders, none of whom had received training in how to talk to analysts. As soon as this point was raised, the group saw that it had found a potential recommendation for the CEO. (The observation came not from the team’s finance expert but from a boundary-spanning HR executive.)

5. Consider multiple categories.

As Lori Weise’s story demonstrates, powerful change can come from transforming people’s perception of a problem. One way to trigger this kind of paradigm shift is to invite people to identify specifically what category of problem they think the group is facing. Is it an incentive problem? An expectations problem? An attitude problem? Then try to suggest other categories.

A manager I know named Jeremiah Zinn did this when he led the product development team of the popular children’s entertainment channel Nickelodeon. The team was launching a promising new app, and lots of kids downloaded it. But actually activating the app was somewhat complicated, because it required logging in to the household’s cable TV service. At that point in the sign-up process, almost every kid dropped out.

Seeing the problem as one of usability, the team put its expertise to work and ran hundreds of A/B tests on various sign-up flows, seeking to make the process less complex. Nothing helped.

The shift came when Zinn realized that the team members had been thinking of the problem too narrowly. They had focused on the kids’ actions, carefully tracking every click and swipe—but they had not explored how the kids felt during the sign-up process. That turned out to be critical. As the team started looking for emotional reactions, it discovered that the request for the cable password made the kids fear getting in trouble: To a 10-year-old kid, a password request signals forbidden territory. Equipped with that insight, Zinn’s team simply added a short video explaining that it was OK to ask parents for the password—and saw a rapid 10-fold increase in the sign-up rate for the app.

By explicitly highlighting how the group thinks about a problem—what is sometimes called metacognition, or thinking about thinking—you can often help people reframe it, even if you don’t have other frames to suggest. And it’s a useful way of sorting through written definitions if you managed to gather them in advance.

Zinn’s story also exposes a typical pitfall in problem solving, first expressed by Abraham Kaplan in his famous law of the instrument: “Give a small boy a hammer, and he will find that everything he encounters needs pounding.” At Nickelodeon, because the team members were usability experts, they defaulted to thinking the problem was one of usability.

6. Analyze positive exceptions.

To find additional problem framings, look to instances when the problem did not occur, asking, “What was different about that situation?” Exploring such positive exceptions, sometimes called bright spots, can often uncover hidden factors whose influence the group may not have considered.

A lawyer I spoke to, for instance, told me that the partners at his firm would occasionally meet to discuss initiatives that might grow their business in the longer term. But to his frustration, the instant one of those meetings ended, he and the other partners went back to focusing on landing the next short-term project. When prompted to think of positive exceptions, he remembered one longer-term initiative that had in fact gone forward.

What was different about that one? I asked. It was that the meeting, unusually, had included not just partners but also an associate who was considered a rising star—and it was she who had pursued the idea. That immediately suggested that talented associates be included in future meetings. The associates felt privileged and energized by being invited to the strategic discussions, and unlike the partners, they had a clear short-term incentive to move on long-term projects—namely, to impress the partners and gain an edge in the competition against their peers.

A checklist for problem diagnosis tends to discourage actual thinking.

Looking at positive exceptions can also make the discussion less threatening. Especially in a large group or other public setting, dissecting a string of failures can quickly become confrontational and make people overly defensive. If, instead, you ask the group’s members to analyze a positive outcome, it becomes easier for them to examine their own behavior.

7. Question the objective.

In the negotiation classic Getting to Yes, Roger Fisher, William L. Ury, and Bruce Patton share the early management thinker Mary Parker Follett’s story about two people fighting over whether to keep a window open or closed. The underlying goals of the two turn out to differ: One person wants fresh air, while the other wants to avoid a draft. Only when these hidden objectives are brought to light through the questions of a third person is the problem resolved—by opening a window in the next room.

That story highlights another way to reframe a problem—by paying explicit attention to the objectives of the parties involved, first clarifying and then challenging them. Weise’s shelter intervention program, for instance, hinged on a shift in the objective, from increasing adoption to keeping more pets with their original owners. The story of Charlotte, too, included a shift in the stated goals of the management team, from teaching innovation skills to boosting employee engagement.

As described in Fred Kaplan’s book The Insurgents, a famous contemporary example is the change in U.S. military doctrine pioneered by General David Petraeus, among others. In traditional warfare, the aim of a battle is to defeat the enemy forces. But Petraeus and his allies argued that when dealing with insurgencies, the army had to pursue a different, broader objective to prevent new enemies from cropping up—namely, get the populace on its side, thereby removing the source of recruits and other forms of local support the insurgency needed to operate in the area. That approach was eventually adopted by the military—because a small group of rogue thinkers took it upon themselves to question the predefined and long-standing objectives of their organization.

CONCLUSION

Powerful as reframing can be, it takes time and practice to get good at it. One senior executive from the defense industry told me, “I was shocked by how difficult it is to reframe problems, but also how effective it is.” As you start to work more with the method, urge your team to trust the process, and be prepared for it to feel messy and confusing at times.

In leading more and more reframing discussions, you may also be tempted to create a diagnostic checklist. I strongly caution you against that—or at least against making the checklist evident to the group you’re engaging with. A checklist for problem diagnosis tends to discourage actual thinking, which of course defeats the very purpose of engaging in reframing. As Neil Gaiman reminds us in The Sandman, tools can be the subtlest of traps.

Finally, combine reframing with real-world testing. The method is ultimately limited by the knowledge and perspectives of the people in the room—and as Steve Blank, of Stanford, and others have repeatedly shown, it is fatal to think you can figure it all out within the comfy confines of your own office. The next time you face a problem, start by reframing it—but don’t wait too long before getting out of the building to observe your customers and prototype your ideas. It is neither thinking nor testing alone, but a marriage of the two, that holds the key to radically better results.